Timeline of Jiuzhai Valley National Park:

1978: Part of the area was protected as a nature reserve after heavy logging which began in 1975. The State Council issued its approval document for the Report on Strengthening the Works of Conservation and Domestication of Giant Pandas, and the report on establishing the Nanping-Jiuzhai Valley Nature Reserve.

1982: The site was proposed as an area of Scenic Beauty and Historic Interest (National Park) by the State Council of the Chinese Government.

1984: Jiuzhai Valley National Park Administration Bureau was established.

1992: UNESCO experts concluded that Jiuzhai Valley “is an incredible place of great natural beauty. It meets the full standards and terms for the Natural Heritage” and was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

1994: The Chinese government named Jiuzhai Valley a state level Forest and Wildlife Nature Reserve and state level Nature Reserve.

1998: Jiuzhai Valley National Park was issued with the Man and Biosphere credential by UNESCO.

2002: Jiuzhai Valley National Park passed the authentication of the Green Globe 21.

2002: Jiuzhai Valley National Park suffered no physical damage in the May 12th Sichuan earthquake but the local economy was badly affected by the resulting downturn in tourism.

Language:

The locals people of Jiuzhai Valley are Tibetan and thus speak the Tibetan language. The local Jiuzhai Valley Tibetan dialect is different to the Lhasa and Amdo Tibetan dialect of the grasslands. The dialects are so different that local people who only speak the local dialect would find it difficult, if not impossible, to communicate (verbally) with people from Lhasa, Aba Town or Qianghai who are not familiar with the Jiuzhai Valley dialect. As the area is increasingly exposed to the outside world, middle-aged and younger people have begun to speak mandarin Chinese. A few Tibetan words will still be lots of fun during your visit.

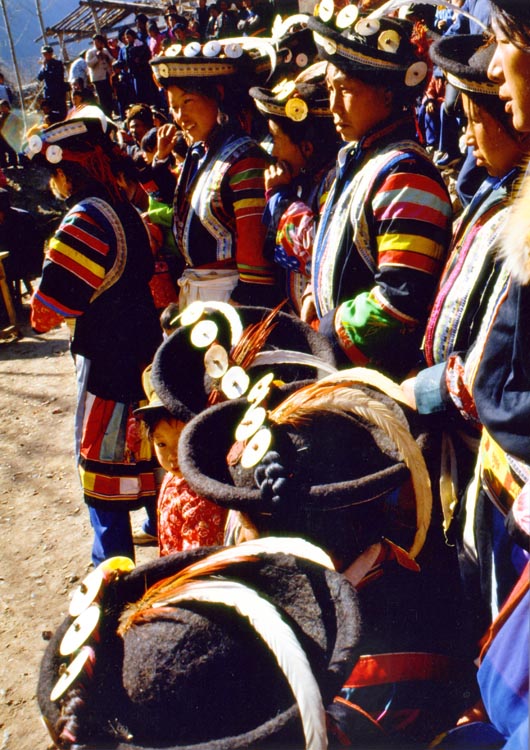

The total population of Jiuzhai Valley National Park is just over 1,000, comprising of over 110 families.

The nine Tibetan Villages of Jiuzhai Valley are He Ye, Jian Pan, Ya Na, Pan Ya, Guo Du, Ze Cha Wa, Hei Jiao, Shu Zheng and Re Xi. Although not officially discovered by the government until 1972, the earliest human activities have been recorded as dating back as early as to the Yin-Shang Period (16th - 11th Century B. C.)

The main villages that are readily accessible to tourists are He Ye, Shu Zheng and Ze Cha Wa along the main routes that cater to tourists, selling various handi-crafts, souvenirs and snacks. There is also Re Xi in the smaller Zha Ru Valley and behind He Ye village are Jian Pan, Pan Ya and Ya Na villages. The Valley's no longer populated villages are Guo Du and Hei Jiao.

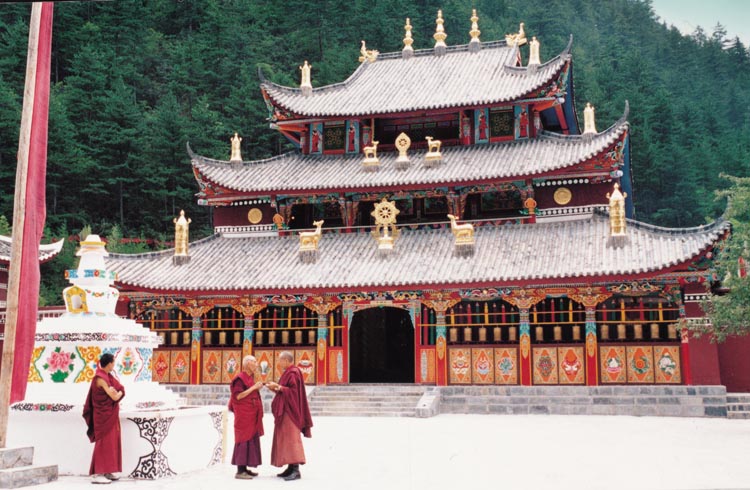

The main religion practiced by the locals is the pre-Buddhism Bon or Benbo-Sec religion. It was introduced to the Aba Prefecture in the 2nd century B.C. It was integrated with primitive local wizardry into the Benbo Sec and became dominant in the 6th Century. In the 7th century, Tibetan Buddhism was introduced to the region. Although through numerous conflicts Buddhism did become prevalent, the Benbo Sec religion has survived and developed, and is now recognised as one of the five sects of Tibetan Buddhism while maintaining unique religious cultural features. There are over 60 Benbo monasteries in the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture.

The Benbo and Tibetan Buddhists worship and make sacrifices to natural Gods. Stupas and prayer wheels (hollow cylinders that contain religious scriptures) can be seen throughout the park, evidence of the local belief that the soul is inherent in all things, including mountains. Prayer wheels come in different sizes and some are turned by hand and others turned by flowing water. One rotation of a prayer wheel equals 100 recitations of religious chants.

Longda can be pieces of cloth (many small pieces of cloth connected by string) or paper with scriptures written on them. The paper longda are thrown in the air, while the cloth ones flutter in the wind or by rivers. The idea of both the longda and the longer guoda is that the wind or water will set the prayers free.

Religious banners or “guoda” in local Tibetan, for different purposes, vary in length from a few to dozens of metres. These are blue, white, red, green and yellow each representing the sky, clouds, life, the natural world (plants, trees, grass) and soil according the five element theory. It is said that families of service men in the Tufan Period (617-907 AD) hung them as army banners on their gates to honour the family. Later these army banners became to bear religious implications and prayer scriptures were written on them. These religious banners are common in the Amdo Tibetan regions and represent an integral combination of the five-element theory and, a proud representation of Tibetan Buddhism.